Onderstaande printversie van het indicatorenboek werd door uw browser gegenereerd, en zal niet steeds optimaal ogen. Via de ingebouwde printfunctie op de website van het Indicatorenboek (ronde knop rechts bovenaan) kan u een printvriendelijke PDF genereren met mooi ogende lay-out.

7.3.3Towards quality-oriented patent indicators

The number of patent applications in itself says something about the extent of the R&D activity but not about the impact of those patents. After all, a patent application does not always lead to a granted patent, and a granted patent does not always lead to follow-up research or economic added value. Quality-oriented patent metrics (as previously proposed by VARIO) are therefore needed to map Flanders' technological progress with regard to patents.

In consultation with ECOOM and the Department EWI, a number of indicators were proposed for this purpose1. Based on an overview of their advantages and drawbacks, as well as their practical feasibility, two of the proposed indicators haven been elaborated in detail: (1) ‘international patent families’ and (2) ‘highly cited’ patents.

1 J. Callaert, M. Du Plessis, B. Van Looy, “Octrooi-gebaseerde kernindicatore”, Nota ECOOM KUleuven, 2022. (not publicly available)

1. International patent families

A patent family is a group of patent publications relating to the same invention by the same applicant. These different publications result from different national and international procedures, for example, patent applications in the United States and Japan. The extent to which a patent is part of an international patent family gives an indication of its anticipated valorization potential. The underlying reasoning is that the significant costs associated with the creation of an international patent family are only incurred when the applicant also expects at least equally significant benefits from the protected technological development.

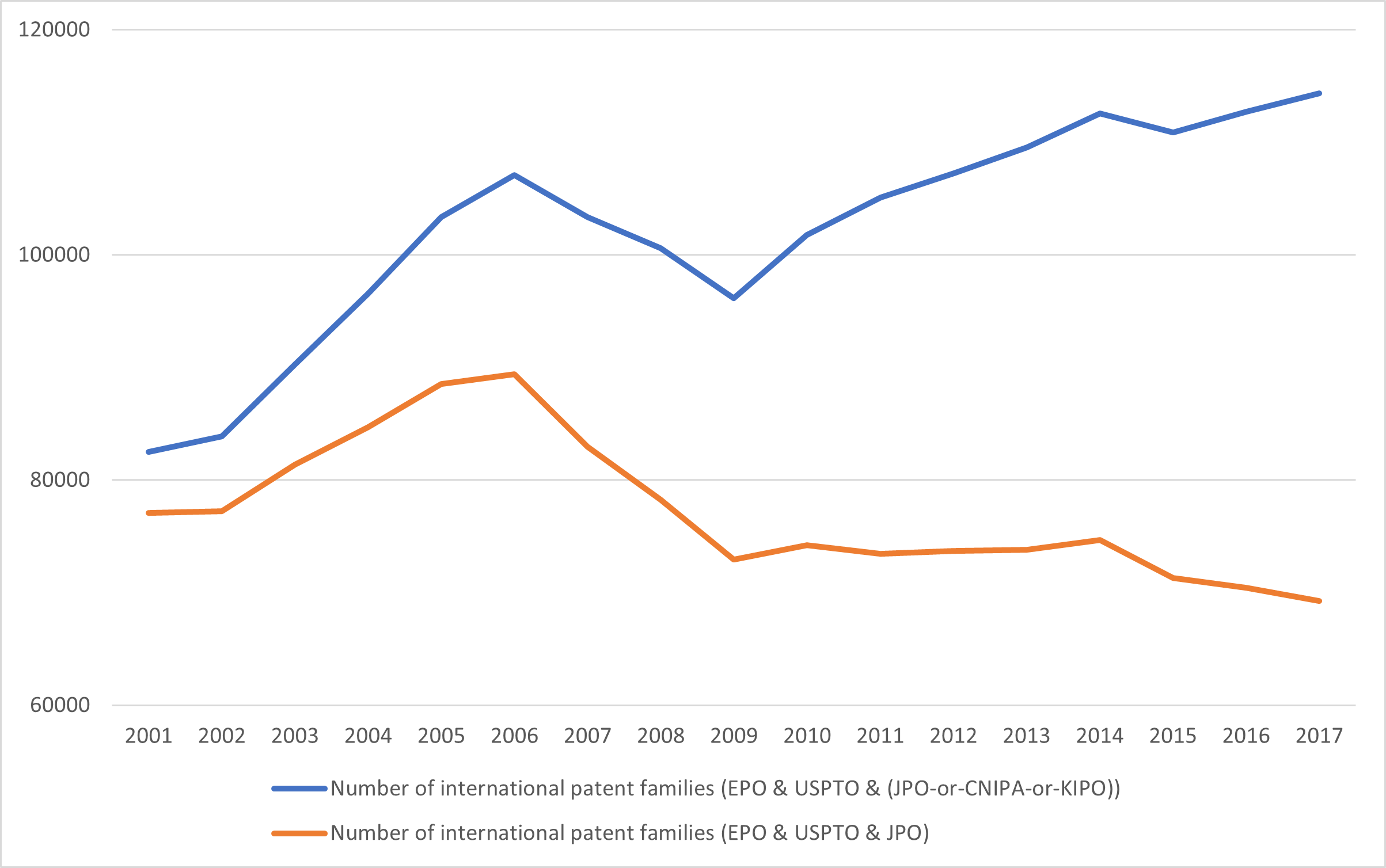

It is common to follow up on the so-called ‘Triadic patent families’ for this purpose. These are patent families with patents in (at least) each of the three largest patent offices i.e. EPO, USPTO and JPO. However, the number of EPO patent applications that are part of a 'triadic patent family' has been declining since 2006 (see Figure 8). This motivated us to consider an alternative metric. In Asia, the importance of patents in China and South Korea is gaining at the expense of Japan.

Sometimes IP5 families are considered, which are patent families with patents in (at least) each of five major patent offices being EPO, USPTO, JPO, CNIPA (China) and KIPO (South Korea). This allocation indeed takes into account major patent offices not covered by the triadic patent families but is extra restrictive. Therefore, ECOOM proposed an alternative that takes into account the patent offices of China and South Korea without being extra restrictive: the number of patents belonging to a patent family with members in US, EU and at least 1 of the 3 following Japan, China, South Korea. In Figure 8, this alternative shows an increasing trend, which is encouraging for the relevance of this choice.

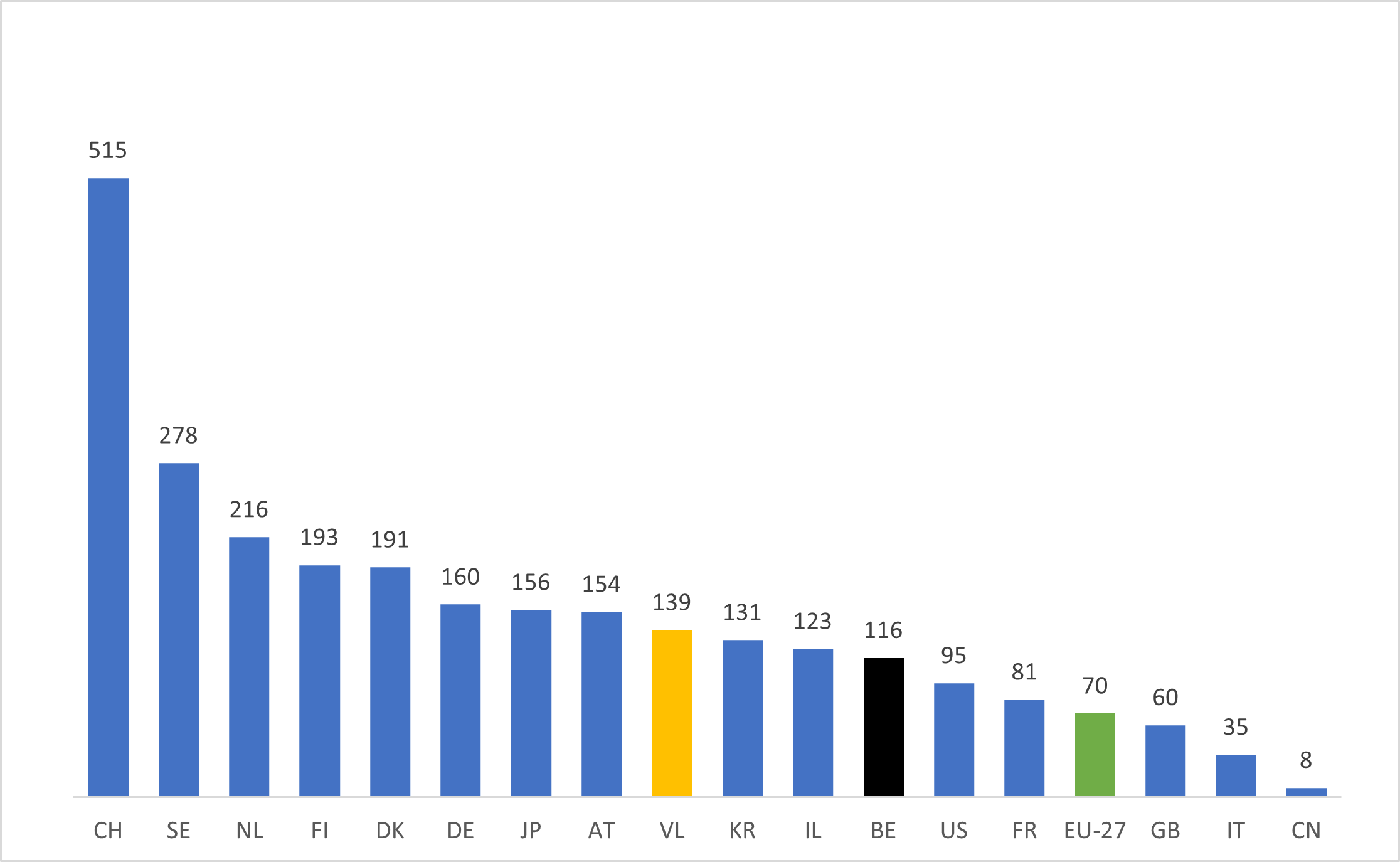

International patent families EPO&USPTO&(JPO-or-CNIPA-or-KIPO): Flanders ranks ‘rather average’ (see Figure 9). This indicator, which is a proxy for economic impact, thus confirms Flanders' position in the VARIO key indicator.

Figuur 8: Trend comparison for international patent families: EPO&USPTO&JPO (‘triadic patent families’) en EPO&USPTO&(JPO-of-CNIPA-of-KIPO)

Source: ECOOM

Figure 9: International comparison of EPO patent applications that are part of an EPO&USPTO&(JPO-or-CNIPA-or-KIPO) patent family, per million population by origin of inventor and/or applicant (2017)

Source: ECOOM

2. Top-5% highly cited patents

Forward citations of patents in other patents are a commonly used indicator for the technological impact of a patent. The importance of patent citations partly parallels that of citations within bibliometrics: something that is cited has an impact. Yet there are differences. Citations in scientific publications serve to frame research findings within the state-of-the-art of and to give recognition to previous scientific work on which the authors build substantively. Citations included by the applicant in a patent description may, in part, perform that task as well. The patent examiner's search report often refers to those, but only if the examiner considers them relevant. In addition, the examiner may himself cite scientific articles or patents that he considers relevant for qualifying the claims according to the legal requirements (new, inventive, susceptible of industrial application and lawful) of a patent. For the applicant, there is not always a clear substantial connection between the patent applied for and the patents cited by the examiner, but there is at least a technical connection according to the patent examiner. In short, patent citations are also a measure of technological impact in the patent system. Finally, whereas self-citations are sometimes excluded within bibliometrics (because of the questionable practice whereby researchers cite themselves to improve their citation scores), they are typically appreciated in patents, because of their rather positive connotation within the patent system: after all, they indicate that technology development within the firm leads to follow-up developments and, in this sense, also capture a form of value-to-the-firm.

The distribution of the number of forward citations per patent is a right-skewed distribution, with a relatively small number of patents having many forward citations and most patents having few forward citations. Patents are considered "highly-cited" if they achieve more than a certain threshold value of forward citation counts in other patents. This threshold value can vary depending on technology domains, patent systems, etc.; parameters can be determined according to the specific research question and context. The indicator here is calculated as the number of patents that fall within a highest percentile (here 95%) in terms of number of forward citations in other patents.

For the figures below, EPO patent applications were considered in a 5-year period. Then, only the patents with at least 1 forward citation (within a 5-year citation window) were considered.

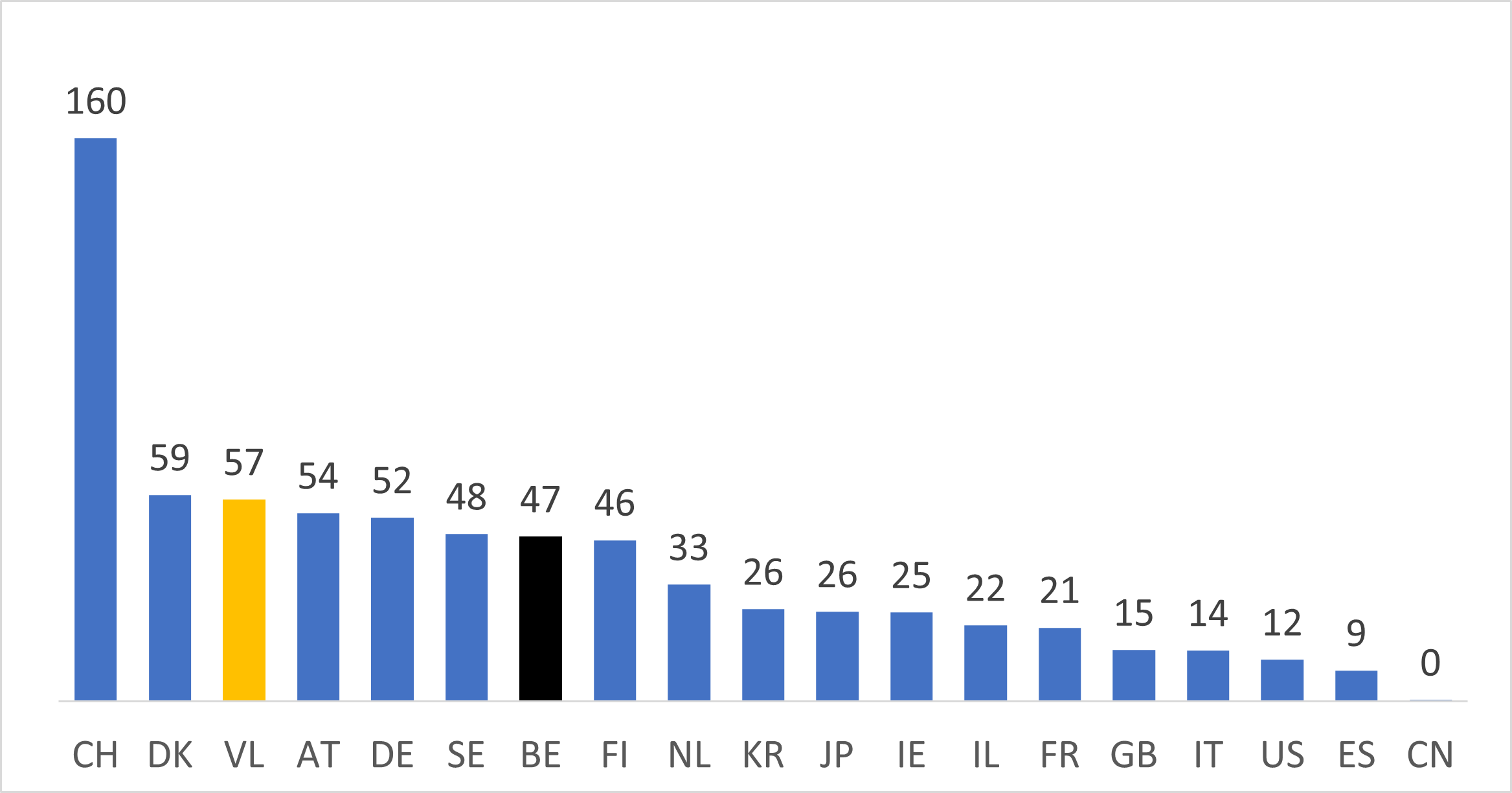

- Flanders ranks third for highly cited patents (top 5%, citation window 5 years), after Switzerland and Denmark (see Figure 10). This high ranking may somewhat positively nuance the interpretation of Flanders' rather average position for the VARIO key indicator for patents.

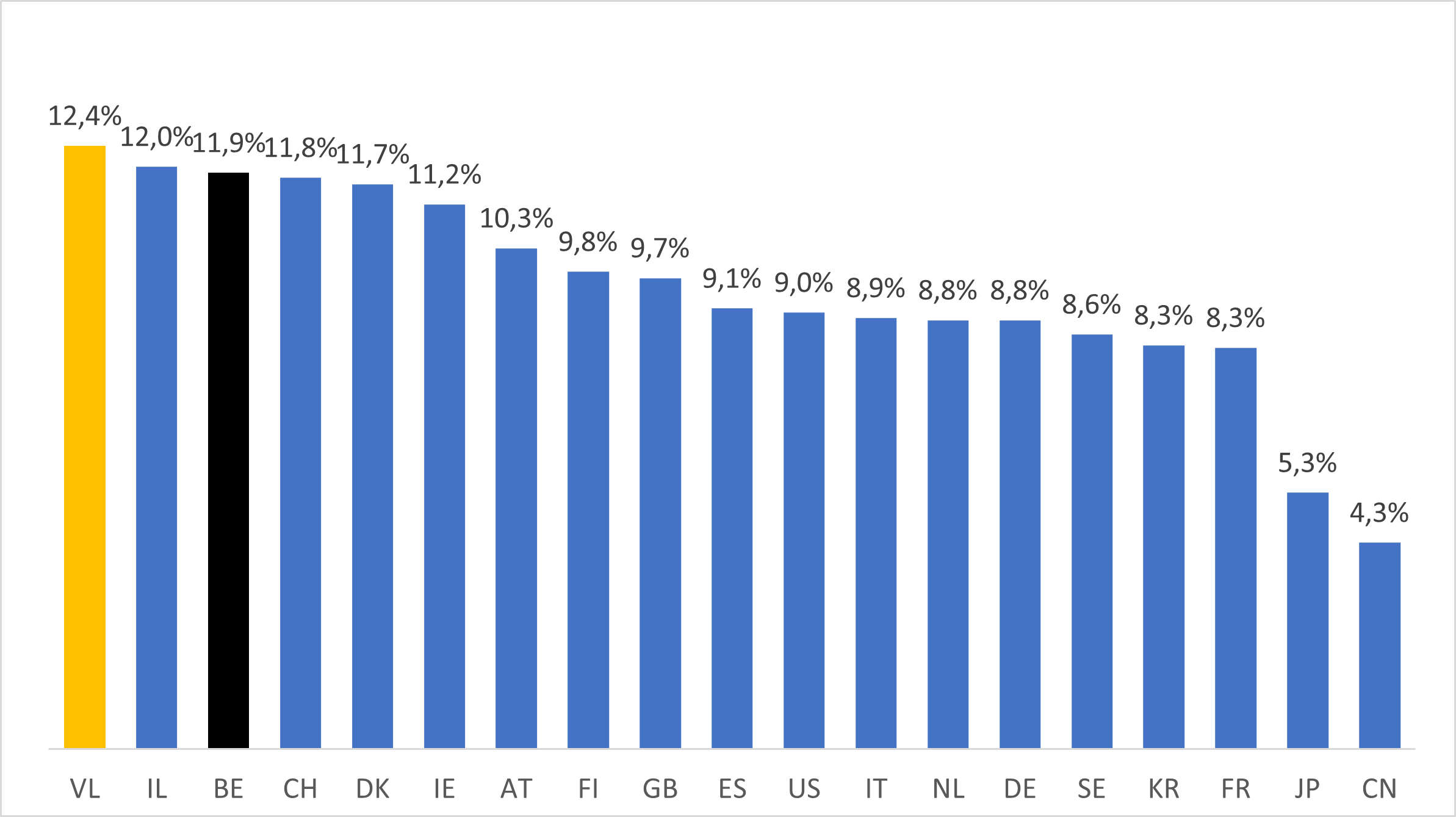

In Figure 11 the share of highly cited patents is standardized with the own patent portfolio of EPO patents with at least 1 citation. Then Flanders even ranks first, before Israel and thus also precedes all VARIO benchmark countries.

Figure 10: International comparison of number of highly cited patents (top 5%, citation time window of 5 years, patents between 2010-2014) per million inhabitants

Source: ECOOM

Figure 11: International comparison of ratio of number of highly cited EPO patents (top 5%, citation time window of 5 years, patents between 2010-2014) to number of EPO patents with at least 1 citation (citation time window of 5 years, patents between 2010-2014) by origin of inventor and/or applicant